“All right—shall we play?”

Light snow falls as Freddie Cox pops into The Barrel Project on a chilly winter morning in London. Safety lab glasses tucked on a beanie, he sets down two plastic jugs filled with what looks like cloudy apple cider and pulls on a pair of latex medical gloves. Alex Wright, who manages this new barrel-aging facility from London Beer Factory, has just come inside after forklifting Bordeaux and Burgundy barrels from a delivery van to storage racks left for now in the street.

Wright set aside two barrels for Cox to play with this morning. One of them, marked “Marry” in white chalk, is filled with LBF’s Big Milk Stout, a hefty 8.8% ABV imperial stout; with tonka beans used somewhere in the brewing process, this particular batch is a collaboration with fellow Bermondsey craft brewery UBREW. Cox is here to add the final touch by pitching one liter of cherry Brettanomyces, a type of wild yeast, into the barrel just more than two weeks after the brewers filled it. Once Cox finishes, it’ll likely be at least a year and maybe more until this beer again sees the light of day.

“Ideally I have a constant supply of CO2 over here. We always purge the barrels before we fill them, so they don’t have any oxygen, and then we just try to keep them as sealed as possible,” Cox says.

“You can put a little bit of sugar in there, as well, as that will create carbon dioxide and push out any oxygen,” says Wright.

This is the first time I’ve ever seen live Brettanomyces—it’s usually just called “brett”—and I’m curious as to how or if the environmental conditions will impact both it and the beer as Cox unplugs the barrel and starts pouring.

“With the brett, it’s not such a big deal because it’s going to chew up that oxygen quite quickly, but when you have yeasts like Lactobacillus and Pediococcus, they don’t like oxygen and just want an anaerobic environment,” Cox continues. “If you pitch all three, usually the brett will chew through the oxygen to begin with, then when there’s no oxygen left Lactobacillus and Pediococcus will take over. But yeah, you want as little oxidation as possible.”

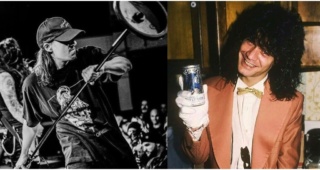

Armed with a biochemistry degree from London South Bank University, Cox joined the London Beer Factory team right after graduation in 2015. He started in the warehouse before earning a promotion to assistant brewer, a role in which he’s carved out a niche as the brewery’s resident scientist and yeast caretaker. “Yeah, the lab is mine,” he says.

Even so, Cox had never done anything like this until the brewery inoculated its first barrels with wild yeasts in mid-2017. When I visit in late November, only 12 of the 180 (and counting) Burgundy and Bordeaux barrels stored at the facility are thus far filled. “It’s really just learning on the job, and I guess that’s kind of what it’s like working with wild yeasts,” Cox says. “None of the barrels work in the same way at all. It can be the exact same barrel producer, the exact same wood, but it all just reacts completely differently. That’s just part of the process.”

The Spark

“It’s not natural fermentation since we take the beer and then add the brett or whiskey chips or whatever it might be, but the reason this whole thing came about was because our Christmas party was a three-day brewery tour in Belgium,” says Wright. “I think there was a moment where we were in 3 Fonteinen and just went, ‘shit, this is good—we’ve got to do this.’”

So they did do it—minus, as Wright noted, the spontaneous fermentation method practiced by those wonderful Belgian lambic breweries.

About three years after brothers Sim and Ed Cotton set up London Beer Factory in Gipsy Hill, an area in South London’s Lambeth borough, the team spun off The Barrel Project in one of the in-demand railway arch units about six miles north in Bermondsey. Those familiar with London’s increasingly prolific craft scene know this particular area as one of its focal points—The Kernel, Anspach & Hobday, Brew By Numbers, Fourpure Brewing Co, and BottleShop are just a few of the notable breweries and beer bars that call Bermondsey home.

“Obviously the fact that it’s on the Bermondsey Beer Mile gives us the opportunity to showcase some of the stuff we’re doing to people that haven’t heard of us,” Wright says. “We turn this into an event space, as well, and there’s just something about barrels and the stories on them. They’re emotive. People like being around them… and it’s cozy.”

[Ed. Note: The “Bermondsey Beer Mile” is the area’s unofficial nickname due to its high density of breweries, most of which open their onsite taprooms on Saturdays. For more on the genesis of Bermondsey’s still-budding beer scene, see this story I wrote a few years ago for BBC Travel.]

Wright and his team do indeed strike a cheerful ambience when they turn this spacious storage facility into a makeshift taproom every Thurday to Saturday (and, soon, possibly Sunday afternoons with live bluegrass performances). Like the barrel-aging project itself, the space is still very much a work in progress when I visit—oh, the joy of transcribing an interview heavily punctuated with pounding nail guns and buzzing power saws—as Wright says a mezzanine level still needs to be built and barrel racks must be lengthened.

Still, it’s amazing what mood lighting and twinkle lights strewn along barrels can accomplish. “The darkness helps hide the fact that this is still an industrial workshop,” Wright says. “It is first and foremost a barrel-aging facility.”

Adventures in Barrelsitting

None of these barrels will be emptied and their contents bottled until at least mid-2018, or about a year after the first ones were corked. At this early stage in the project—again, more than 150 barrels are still empty that day, with more on the way—no two barrels have identical contents, and there are no plans to try and replicate any brews down the road, either.

LBF have filled the barrels with stouts, Flemish reds, and märzens, though other beer styles are in the cards, too. Cox wants to age something with sweet oranges; Wright laments a failed forage for sloes in Dorset. “I keep telling the brewer that what I’d really like is a high-percentage, Trappist-style blonde, and then put apricots in the barrel with it,” Wright says. “I’m desperate for him to sign off on it.”

Related: The Culture of Beer—A London Pub Chat with Matthew Curtis and Will Hawkes

Once they’re ready these beers are destined for 750ml bottles, which means that each of these 225-liter (Bordeaux) and 228-liter (Burgundy) barrels will yield no more than about 300 bottles, and likely fewer, depending on such factors as bottling spillage and how much beer soaks into the wood. “When people talk about small-batch beers they’re usually talking about thousands of bottles, but these will be really small batches,” Wright says. “I’d like every bottle to have its own unique story and label, and almost become like a collector’s item. I think that’d be a really nice thing, and obviously I’d get to keep one for myself. If you’re making it you have to try it, and that’s part of the fun of it.”

In this case Wright, a former chef who catered film and television sets, doesn’t actually brew the beers, but rather is something of their surrogate father once the brewery drops them off in Bermondsey. He names them, in fact, and knows the stories behind each one’s development.

“I ended up calling them all [people] names because we try to make them all different combinations. I do it like storms, so the first one starts with an A, the second B, C, D, and so on,” he says. “We haven’t actually thought about the packaging, because obviously this stuff is going to be in there for awhile, but we don’t want to do any blending. We’re just going to bottle straight from the barrel and sell them as the name.”

Wright named the first barrel-aged batch “Al” after, well, himself, and calls one of the most recent brews “Lena.” The latter is another collaboration with UBREW, this one featuring whiskey-soaked maple chips added to LBF’s Milk Stout and aged in a Bordeaux barrel. Why Lena? “I named it after my mum,” he says. “I love whiskey, and my whole family loves whiskey, so it just kind of reminded me of home.”

One barrel is filled with a blend of Big Milk Stout and Flemish red, mostly just because there was some leftover stout and the barrel of red wasn’t full. “It may turn out to be absolute shit, but who knows?” admits Wright. (This beer blend reminds me of the Clutch / New Belgium collaboration, which is definitely not absolute shit.)

Another one, called “Greg,” was a bit of a problem child. After the brett was already pitched the beer overflowed, prompting the team to twice siphon it into other barrels and top the barrel up again due to oxidation concerns. Appropriately, Greg’s barrel is marked “Double Siphon BRETT unknown.”

“It’s all good fun,” says Wright, who stands at the archway’s entrance watching the swirling snow on Druid Street. “It’s the best job in the world, really, isn’t it?”

Cox caps the brett and peels off the latex gloves. “Yeah, it felt very dramatic, you know. Pitching barrels in the snow.”

###

The Barrel Project is located at 80 Druid Street in Bermondsey, London. Open Thursday and Friday 6pm – 11pm, and Saturday 12pm – 11pm. +44 20 8670 7054.

All photos copyright Beer Travelist and cannot be used or republished without permission.