The most significant brew of John Wei’s life almost didn’t happen.

In Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Wei fidgeted through an agitated night of sleep, second-guessing his plans, wondering whether he should play it safe instead of making what he calls a “ballsy move” come morning. The thirtysomething Singaporean was in the midst of brewing his first beers as a professional brewer, and as advice from friends and peers swung from one end of the pendulum to the other, the crushing foot of expectation pressed harder and harder.

“People expect me to brew a different kind of beer,” Wei says. “I think my reputation was a little at stake because if I had launched with just standard beers, I think that nobody would have respected me anymore.”

At the same time, few believed that including a wild IPA—that is, an India Pale Ale brewed with a wild yeast, in this case Saccharomyces, that can be somewhat unpredictable—amongst a new brewery’s four introductory beers was wise. An easy-drinking summer ale was arguably the only beer with mass appeal, at least for a nascent market like Singapore, in Brewlander & Co.’s debut lineup: the others were a saison and double IPA.

“I had cold feet, and no idea how I was going to explain and sell a wild IPA to vendors, much less to customers,” admits Wei. “I decided to trust my instincts.”

A Night at the Hawker

In equatorial Singapore, where the average year-round temperature is around 80 Fahrenheit (27 C) with high humidity, the weather outside can be particularly frightful at times during the even-hotter season. You feel it most at night, when the furnace-like heat doesn’t drop as much as it usually does after sundown, and when the afternoon’s sticky, stubborn humidity lingers on almost unabated. Sometimes, after a temporary early-evening dip, it even warms back up as the night wears on. Bloody hell.

Oscillating ceiling fans mounted here and there at Chinatown Complex Market & Food Centre do little to ease the pain on a balmy Thursday evening in June; they just spread it. It’s business as usual, however, at this sprawling old-school hawker centre, home to more than 200 food vendors collectively cooking up multiple versions of just about every local specialty one can imagine. Skewered meats sizzle on gas grills in one stall. Auntie (“auntie” and “uncle” are the local honorifics for seniors) chops roasted duck with a cleaver at another. An orchestra of metal spatulas scraping woks resounds in this busy corner and that as these hawker chefs, unsung heroes nearing the end of another long hot day, methodically sear and serve seasonal greens and rice and proteins and breads and noodles a hundred different ways.

Life in Singapore revolves around food—good food—and the hawker centre is where locals go to get it hot, fresh, and cheap. More than just feeding grounds, however, the more than 100 island-wide hawker centres function as Singapore’s de facto community gathering spaces. You go there to eat, sure, but you also go to play cards, read the newspaper, maybe nap, maybe get drunk, definitely to shoot the shit.

Perhaps you play checkers, too, as a few uncles do a few tables behind me and Wei. We’re on the second floor of Chinatown Complex, where as many food vendors wind things down as the clock ticks towards 8pm, the craft beer hawkers at hidden Smith Street Taps pour draft beers from their stall’s 12 taps for a few more hours. Wei sips a bottle of Yeastie Boys Gunnamatta IPA from Smith Street’s adjacent sister stall, The Good Beer Company, while I tuck into a pint of W-IPA from Minoh Beer, the premier craft brewery in Osaka, Japan.

It’s been almost three months since Wei and his local partners launched Brewlander & Co, the latest in a wave of new craft breweries sweeping across Singapore over the past few years. The brewery’s second batch of beers, which include a porter, New England wheat ale, and session IPA, landed a week or two prior to our meeting and are fast disappearing. “We are learning; we’re a work in progress,” Wei says. “I don’t want to say that we’ve arrived. There are a lot of supportive people who congratulate me, but we have not achieved a single thing.”

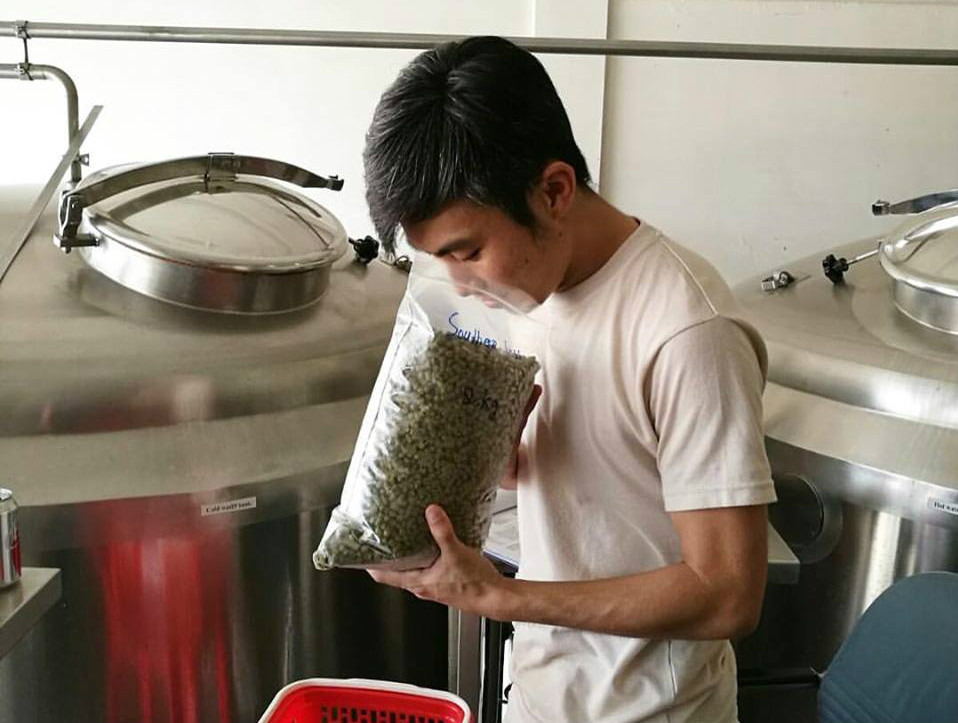

At the moment Wei brews in Phnom Penh at Kingdom Breweries every month-and-a-half or so. He spends two to three weeks in the city for each brewing session, arriving on a Sunday night, working full days through the week, then flying back home to be with his wife and two young children over the weekend before returning again on Sunday. Such is the life of a contract brewer, or to use the sexier term, a “gypsy brewer”; that is, a brewer without a brewery of his or her own who produces their beers at a host facility.

Thus far Wei cranks out around 17,500 liters during each of these sessions, sometimes knocking out two beers on the same day. “After I finish the brewing, every other day is critically important,” he explains. “I come in at 8am, go to the lab, take samples, look at cell counts, and see if there are any infections or bacteria. I then have to see whether fermentation is going accordingly and take gravity readings, and then, most important, is tasting the beer.”

Every professional brewer worth their salt trains their palate over time to detect subtle differences in acidity, bitterness, body, and other factors that impact beer flavor. Like any learned skill it’s an evolving process—practice makes perfect, as they say. It may be early days for Brewlander & Co, but before turning pro Wei honed his beery taste buds as a homebrewer, scoring a number of awards over the years at Singapore’s annual homebrewing competition, The iBrew Challenge. Furthermore, he passed the Beer Judge Certification Program (BJCP) entrance and tasting exams on his first try, and is now BJCP’s Asia representative.

“I taste my beer every day, which is a habit from homebrewing. Even though it tastes like shit, it’s just conditioning your palate to know that it’s supposed to taste like this on the first day, like that on the second day, and so on,” Wei says. “It’s learning how different beers are supposed to taste at different times, and seeing how the yeasts behave differently. It’s education on a scientific and on a sensory level, because at the end of the day you have to trust your taste and senses.”

The Price is Right

In Singapore folks routinely, happily, blow $20 on piss cup-sized glasses of wine and $25 on fancy one-gulp cocktails, yet on occasion craft beer suffers from a pricing stigma that somehow eludes these other alcoholic tipples. With that said, due to issues that range from vexing booze taxation to high rent at retail spaces, some of the premium imported stuff certainly comes with a, shall we say, challenging ransom.

For example, while writing this story I spot-checked prices at two of Singapore’s most well-known online bottle shops. To cite just two examples, a 330ml bottle of Siren Craft Brew’s Primal Cut was available at one shop for SG$13.40; at Honest Brew, one of my go-to online craft beer retailers in the UK, the same beer was £3.79, or about SG$6.70. A can of Beavertown Brewery’s Gamma Ray at the other Singapore shop was SG$10; at Honest Brew, £2.49 or SG$4.40.

I realize I’m cherry-picking here, but in general one can expect top-shelf imports to cost at least twice as much in Singapore as they do in the home country; bombers (big bottles) tend to have even higher mark-ups. A 750ml bottle of Founders Brewing Co’s Lizard of Koz, for instance, retailed in Singapore for SG$50.

Related: Download the Free Beer Travelist Guide to Singapore

In short, it’s true that craft beer isn’t “cheap” here, but then the limited, more esoteric craft beers aren’t “cheap” anywhere. As most dedicated beer enthusiasts understand, there are valid reasons why certain beers are priced a certain way, just as there are valid reasons why certain cuts of beef or sashimi are priced differently than others. Incidentally, those $50 bottles of Lizard of Koz were sold out when I checked.

Aside from bottles and cans, you will usually pay between SG$12 – $18 for most pints of craft at most beer bars. Pint sizes vary, of course, and some venues tack an extra 7-percent GST (Goods and Services Tax) and 10-percent service charge on top of it. It may sound pricey, and some venues are indeed having a laugh at their customers’ expense. All things considered, however—the costs of exporting, importing, distributing, finally pouring, etc—$15 for a pint of the good stuff isn’t bad, and is in my view a far better value than a precious $25 cocktail. We don’t usually tip in Singapore, either, unless it’s automatically added to the bill.

Keep those pricing realities in mind as we turn back to Brewlander & Co, which even though it produces its beers in Cambodia (for now; more on that later) is a proudly Singaporean brewery with a Singaporean brewer, Wei, backed by Singaporean partners. “I can accept if somebody gives my beer one star [on Untappd or RateBeer] and says it’s shit; that pushes me to improve,” says Wei. “But when somebody gives it four-and-a-half stars with all good comments, but then undermines all those good things by saying that they don’t understand why the price for a local beer is the same as one that is imported, I take it as an insult. I feel very disappointed by that.”

In Singapore bottles of 330ml Brewlander beers retail for $8 – $11, which is around the same price as the widely distributed Hitachino Nest from Japan’s Kiuchi Brewery. In other words, Brewlander sells at or below the going rate of imported craft—and to some, especially those who may be new to craft beer, that doesn’t make sense. “It’s very hard for me to explain [the price] to a customer who I don’t know. I’d have to do so by putting my beers in context with other ones, and I don’t want to do that,” says Wei.

However, when I ask Wei to describe what goes into a $9 bottle of Brewlander’s crisp, beautifully balanced saison Pride, he provides an honest, thoughtful answer that starts, appropriately, with a hawker centre analogy. This is clearly a topic about which Wei feels strongly, so though I’ve edited some of his response for clarity and length I have included most of it.

I hope this helps some readers better understand why certain beers–not just those Brewlander produces–cost a certain amount, and that Wei’s impassioned explanation dispels the myth that a high-quality local beer must always cost less than one that’s imported.

“When I first got married it was just me and my wife, so for us to go to a hawker centre and have two meals—two economy rices with two meats, a veg, some white rice—it would cost less than $7 for the both of us,” he says. “If we cooked the same thing at home, it would have cost a lot more than that because, in cooking and production, everything comes down to economies of scale.”

“In terms of production, Brewlander doesn’t have the economies of scale, so that’s why we’re not as cheap as some US brands. If I have a brewery in the States, I’m going to produce for a lot cheaper there because malt is local, water is local, yeast is local, hops are local—everything you source is local, and after you ship the beers to Singapore it’s still cheaper.”

“This is all my choice, but for Brewlander I buy malts from the UK, hops from the States and New Zealand, and for the yeasts I air-freight liquid cultures in from the States. I do this for every brew. I can use the yeasts for multiple generations, but I’m not brewing back-to-back enough to enjoy that. Eventually, when we get there, I can use a yeast 10 times before I buy a new pitch, but for now every batch uses a new pitch.”

“So I pay freight to send the ingredients over, and the taxation here is crazy. I can only speak for myself, but I pay a 25-percent tax on whatever ingredients I import into Cambodia. Labor in Cambodia is cheap, but electricity is more than two-and-a-half times more expensive than in Singapore.”

Wei mentions that per the terms of his agreement with Kingdom Breweries he pays a flat fee for each brewing session, then must cover additional fees for any extra use of the facilities. It costs roughly four times as much to store beers in a refrigerated warehouse in Cambodia than it does in Singapore due to the electricity costs, as well.

“We are also gypsy brewing, so there’s a middle man there that earns a certain margin. I knew from Day One that I can’t engage in any price wars because I’ll never be as cheap as others. I don’t want to be cheap, anyway, because I don’t think it reflects what we’re trying to build.”

“I don’t think we’re expensive; I think we’re fair. If you are paying $1 for a certain beer, what I would like to think is that you’re getting a 60 cents value. I would like to sell Brewlander to you for $1.20, but give you a value of $1.50. It comes back to this idea that since it’s local it has be cheaper, and that’s something that I think is sad.”

While explaining the costs equation, Wei forgets to mention his own time and compensation.

Brothers in Cask

A few days before we meet at Smith Street Taps I run into Wei at Jack Is Not Dull, a pop-up cask ale bar managed by Casey Choo and Kevin Ngan, whose other bars include Good Luck Beerhouse. Wei is there to help clean the cask lines, haul the casks up a few flights of stairs, and to show Choo how to pump a perfect glass of cask ale, or to be specific, how to pump a glass of Brewlander cask ale.

“You package cask ales half done, so you have to trust your skill and the pub to treat the beer properly because the beer finishes in the vessel,” says Wei, a fierce cask advocate. “I’m very particular about my cask ales, and we’re only talking about eights casks [for Jack Is Not Dull]. I didn’t have to make those, but for me it’s a movement and something we’re trying to do to grow the scene. I also did it out of gratitude for Kevin, who has not only supported us, but also other Singapore breweries.”

Wei met Ngan in December, a few months before Brewlander’s debut and a few after Ngan opened Good Luck Beerhouse on Haji Lane. “He is very supportive of local brands and is a guy that doesn’t just buy the beer,” Wei says. “He wants to be very clear that he’s supporting somebody that he believes in. He wants to see the brewery, get to know the brewer, taste the beer, and feel like it’s a brand and movement that he can get behind.”

To wit, Ngan accompanied Wei to Phnom Penh for one of his pre-launch brewing sessions to try the beers. “He placed an order on the spot,” says Wei. “That gave me a lot of confidence, because for a guy who has never sold a single bottle of beer to bring in the equivalent of 24,000 bottles on the very first batch… man, you get butterflies in your stomach.”

The day after returning to Singapore Wei brought Ngan a bottle of Love, the wild IPA that he almost didn’t brew. “After he tasted it, right there and then he increased his order and told me not to worry.”

Brewlander Runs Wild

Brewed with Crisp Extra Pale Maris Otter malts, flaked wheat and oats, “bucket loads” of Citra, Mosaic, and Hallertau Blanc hops, and the aforementioned Saccharomyces yeast, Love is Brewlander’s highest rated beer on Untappd and its second-highest (just behind Courage, the double IPA) on RateBeer. “It sold out within three weeks, and that’s the beer I thought would take the longest to sell,” says Wei. “We’ve had a few vendors call and try to buy everything we have left.”

It’s not just Singapore’s small community of beer enthusiasts making supplies scarce, either. “More than 70-percent of the people who are buying our beers are not from the ‘beer geek’ crowd, and the one beer that they all unanimously say is the best is the wild IPA,” Wei says. “It’s crazy, and it’s humbling, because I don’t want to put myself into that geeky cult status. I want beer to be inclusive, not exclusive.”

Despite a projected total output of just 140,000 liters in its first year, Brewlander & Co already exports to Malaysia, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. The potential for growth is clearly there, and has Wei thinking about a future brewery of his own. “I would like to have a place I can call home—my own playground, my own backyard where I can just go and brew and have fun,” he says. “I’m not going to say we’re not going to do it. It’s in our business plan, and when the time is right it’s something we’ll definitely explore.”

Wei is quick to point out, however, that that time is not now or next month, or (probably) not this year, or maybe even next. “I want to make sure we get our beers right first. My goals are making sure that every beer tastes how it’s supposed to taste. I want to get Brewlander to a point where people recognize that most of our beers are good, regardless of the beer style,” he says.

“Everyone has been complimentary, but there’s one, maybe two beers that I’m not happy with; they’re not bad, but they could be better. It’s not about meeting people’s standards. It’s about meeting my own standards, and I set very high standards for myself.”

*******

Brewlander & Co is available on tap and/or by the bottle at many of Singapore’s finest beer bars and bottle shops, including Sixteen Ounces, Booze Pharma-C, Freehouse, and Hop Shop.

For a deeper dive into Singapore’s vibrant beer scene, download the free Beer Travelist Guide to Singapore, which is packed with tips on the Lion City’s best beer bars and brewpubs, bottle shops, beer-friendly restaurants, and more. You’ll score exclusive discounts to some of the island’s best watering holes, too, including some mentioned in this story.

Photo credit for the third photo: Wichawon Lowroongroj / Shutterstock.com. Photos of John Wei courtesy of Brewlander & Co; all other photos taken by the author and cannot be reused or reprinted.

Full Disclosure: Brewlander & Co donated a keg for Beer Travelist’s Singapore launch party in May 2017. This fact did not influence coverage in any way; we would have written this story even if they had told us to go to hell.