“All right, all right… are you feeling it? Are you feeling it?!”

Public displays of enthusiasm, genuine or not, rarely come easily, but I’ll do anything to please Tom from Perth. I manage half-hearted affirmation that, yes, I am feeling it, this green wave swelling towards us in The Wreck’s late-morning surf.

“Okay, paddle… paddle… paddle harder! More like a banana, more like a banana… and pop up!”

Tom from Perth, treading ocean as effortlessly as breathing, thrusts my foam board forward like father pushing son on his first crack at a bike without training wheels. And like most kids’ early trainer-less attempts I’m off the side of the board, again, just shortly after dad—that is, Tom from Perth—lets go.

Tom from Perth has an implausibly laid-back aura and appearance. His long, stringy blonde hair falls down past narrow shoulders, and a thin ‘70s-style mustache floats lazily above his thin upper lip. His eyes are ocean blue, his teeth remarkably white. He is roughly 98-percent muscle, give but not take two percent.

Tom is an ocean man, an amphibious being clearly more at ease in water than on land. It would have been only mildly surprising if he walked on the ocean to reach the surf breaks. “I don’t know about you guys, but I’m ready to get wet! Woooooo!,” he exclaims when we first reach the beach, flopping back-first into the water, arms outstretched as if nailed to a cross. There’s nothing else to do but feign enthusiasm and flop in with far less grace after him.

Tom speaks with a uniquely slack, Western Australian-meets-Californian-surfer drawl. Although I’ve grown accustomed to the local lingua after spending three of the past 12 months in Byron Bay, Tom’s accent is so thick that I understand very little of what he says during the first half of the surfing lesson. All I can do is follow cues and nod and laugh (un)knowingly when it seems appropriate to do so.

After the lesson—after spending about 90 minutes in Byron’s particularly clean, cold, crystalline swath of Pacific—Tom from Perth and I retreat to his “office” in a beachside backpacker hostel. I am crusted with salt, mildly sunburned, and exhausted. Tom, however, looks exactly the same as he did when I first checked in. He is somehow completely dry, from long hair to bare feet, and as he plops back into a creaking swivel chair looks as though he hasn’t expelled one joule of energy in weeks.

Tom from Perth is one embodiment of Byron Bay, a complex, multi-faceted town at Australia’s easternmost point, a place where surfing is a right and way of everyday life; locals of all ages slip into the ocean like seals. Here Tom is, to coin a phrase that village brewery Stone & Wood uses with great marketing effect, the way it should be. Before we look at the brewery, however, further context on its habitat feels appropriate.

A Corner of the Globe That’s a Real Trip

Byron Bay is the crown jewel of Byron Shire, an area encompassing more than 40 towns and localities in the Northern Rivers region. Each of these places is quite small—with a permanent population of around 10,000, Byron is the shire’s largest town. In insane contrast, more than two million visitors descend upon the town every year; that’s at least 200 for every one resident.

Byron is much more than just an everyday town or problematic tourist hotspot, however. To many Australians it is a view of paradise, and to locals it is a binding, living community doctrine, this imperfect utopian dream unfolding in one of the most varied, almost unfairly magnificent patches of land one will ever come across. To one side is glorious, undeveloped, rugged beachfront and refreshingly pristine Pacific Ocean, waters teeming with pods of dolphins and migrating whales from roughly June through August. Due west of Byron, arcadian hinterland unfurls in tumbling hills, verdant pastures, and dense forests scented with the minty, earthy fragrance of eucalyptus.

Byron and the surrounding Northern Rivers are simply environmental marvels.

Downtown Byron itself, though not without charm, is more grower than stunner. It is not, in other words, the unmistakably cute and quaint shire town you’re looking for—that would be about 15 kilometers inland at Bangalow.

Beyond natural bounty, Byron is a lucrative brand with national and sometimes international reach. For starters, there is the Byron Bay Chili Co, Byron Bay Chocolate Co, Byron Bay Hat Co, Byron Bay Macadamia Muesli, Byron Bay Peanut Butter Co, and Byron Bay Coffee Co. There is also Byron Bay Brewery, which major Australasian food and beverage company Lion (which owns Tooheys, Hahn, Little Creatures, many more) acquired in 2015 as much for its marketable Byron branding as for its so-so beer.

Byron is the face of the continent’s largest annual music festival, Splendour in the Grass, a modest Australian approximation of Glastonbury; doing Splendour is as much a rite of passage for young Aussies as doing Glasto is for their UK peers. Splendour comes to town every July—actually it comes to the North Byron Parklands in Yelgun, about 30 kilometers up the road. When it does, Byron’s annual off-season breather, which generally spans the cooler (though still sublime) May to August months, is interrupted by a long four-day weekend that brings more than 40,000 festival-goers.

Related: In Margaret River Wine Country, Bloody Good Fun with Beer at Rocky Ridge Brewing

It’s fascinating to see downtown Byron transform overnight from low- to high-tourism season mode, then back again after the splendor of Splendour subsides. Local businesses, residents, buskers, and performers of all kinds know exactly how to milk the cash cow in such a way that everybody leaves the madness (mostly) happy.

Visitors get their idealized Byron Experience—the kooky sixtysomething couple lighting up the dancefloor at The Rails, the stormtrooper playing saxophone in a graffitied laneway, the beachside drum circles, the acoustic jam sessions on Jonson Street. For playing the part for a few days beneath the goring foot of mass tourism, locals earn a welcomed financial shot to the bottom line.

Byron is aggressively and, in most ways, refreshingly progressive. To cite just a few examples, a major and increasingly successful push to make Byron Shire businesses plastic-free continues. Renewable energy providers like Enova Community Energy, Australia’s first community-owned electricity company, pitch to a receptive audience. In 2016, Byron Shire residents filled seven of its council’s nine seats with councillors who are either independent or from the Greens party. And according to one recent survey from the Nature Conservation Council, 87 percent of Byron Shire residents rated actions to address climate change and deforestation as two of their main concerns in upcoming elections.

On infrequent occasion the passionate progressivism, support it though I do, can border on the saintly. I refer of course to grocery shopping at Woolworths (“Woolies”), the national supermarket chain with an impressive new signature venue in downtown Byron. Specifically, there are times when the person behind you at the checkout counter will not disguise their contempt (or approval) as they survey your purchases, as if whatever you chucked into your cart that day is a window into your soul. Kombucha, kefir, all-organic everything? Well done! Frozen vegetables, Oreos, nothing organic? Consumerist pig!

Despite its hippie, new-agey notoriety and reputation as a hideout for writers, artists, and creative types—and there are those—Byron is secret wealth, or maybe not-so-secret-anymore wealth. Day-to-day costs like groceries, in particular, but also eating and boozing out certainly depress some of the fun in the surf. In terms of house ownership, this year Byron earned unwanted recognition for having Australia’s priciest median house cost at a knee-buckling $987,500. That is a 64-percent increase over the past five years, compared to “just” 44 percent in Sydney and Melbourne; the median price has actually increased at least 10 percent every year for the past two decades, which is nuts.

Older, monied, now-former Sydneysiders and Melburnians are apparently one demographic driving the surge, but celebrities like actor and Byron resident Chris Hemsworth certainly hike that median, too. With a now-discarded $7 million home already in their back pocket, Hemsworth and model wife Elsa Pataky dished out at least $9 million on a massive custom-built fortress in the Broken Head nature reserve. Just to be clear, though he has a funny way of showing it the actor says he “feels gross” about his wealth; some locals feel gross about it, too.

Legendary surf spot, tourism and live music staple, marketable brand, new-age progressive, furtive fat cat—Byron plays its roles with aplomb. A year ago I hardly knew the place existed, and while three months reveals but a surface scratch for this outsider, it’s long enough to paint semi-comfortably between big-picture lines and to appreciate certain idiosyncrasies.

After a while you learn Woolies’ sushi department makes way too many chicken rolls, and plan for Suffolk Bakery’s brilliant marmite-cheese scrolls to usually be gone by 10:30am at the latest. You start setting your food clock to Mexican Monday at The Park Hotel; pizza (Pizza Paradiso), taco (Chupacabra), and curry (Yellow Flower) Tuesday; oysters Wednesday at The Balcony; chicken schnitzel Thursday at The Park; and frothy Friday at Main Street Burger Bar.

You learn a great deal about the shire’s state of mind by reading The Byron Shire Echo every week, and by listening to Bay FM at least a little every day. You come to understand that live music every night for the past 30 years straight is one reason why The Rails is one of the best bars anywhere.

It didn’t take long at all, however, to learn why Stone & Wood, which set up in Byron in 2008, is more than just one of the most locally beloved breweries I’ve ever come across. This village brewery, as its staff often calls it, is as analogous to its community’s everyday life as the daily surf report.

It’s a bond that goes well beyond beer.

The Village Brewer

Saturday, June 9, 2018, a few days after I first set foot in Byron. The clock ticks towards 10pm on this cool clear night, and it feels like everybody in town is at Festival of the Stone and won’t be leaving until it’s over. The bands are done, but the DJ is still ripping through classic pop hits and by the time he spins Paul Simon’s “You Can Call Me Al” everybody—everybody—is still dancing joyously with their mates, uninhibited, singing along, just as they’ve done all night long.

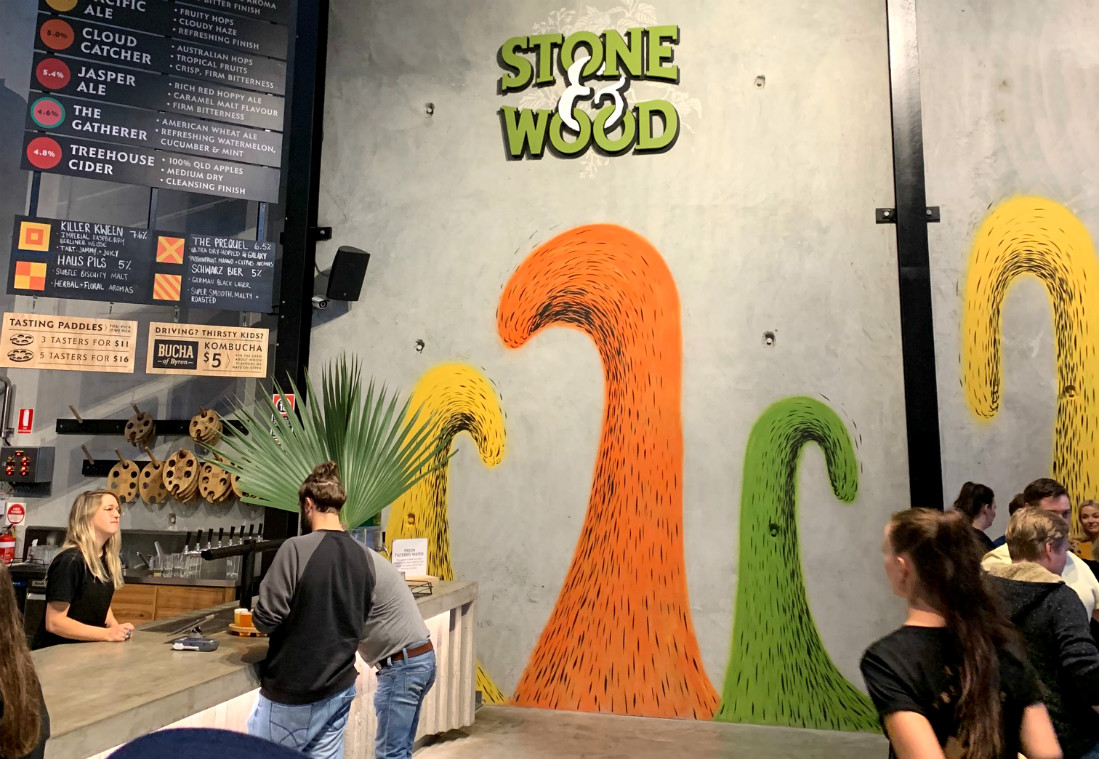

It is a wild, raucous, life-affirming scene at Stone & Wood’s original brewery in Byron Bay, one of those times when it feels incredible just to be alive. It’s one with an unmistakably communal feel, too. There are likely a handful of out-of-towners here (including me and my wife), but Stone & Wood’s signature annual fundraising event is first and foremost a local affair. Everybody seems to know somebody, and some probably know just about everybody.

Festival of the Stone is a big deal. The outset of cooler and wetter winter has quelled the tourism wave for awhile, so in a way this is a time for locals to exhale and blow off steam as a community. This year it’s a big day for Big Scrub Landcare, a local charity working to restore and care for highly endangered Byron Shire rainforest. Stone & Wood chose Big Scrub as the recipient of all beer and merch proceeds from the 2018 festival, which turns out to be a $17K donation via the brewery’s not-for-profit inGrained Foundation.

A year later, Festival of the Stone raises $10,500 for the Mullumbimby & District Neighbourhood Centre, which does everything from support women affected by domestic violence to helping at-risk children and those struggling with mental health issues.

It’s a big day for good beer, too. Stone & Wood’s everyday range is poured at the event, but Festival of the Stone notably marks the much-anticipated annual release of Stone Beer. To accentuate this boozy porter’s roasty aroma and flavors, brewers pitch wood-fired stones in the kettle at an all-day party for the brewery’s whole staff. In 2018, Stone & Wood for the second time released a limited amount of Stone Beer aged for a year in port and whiskey barrels—packaged in ceramic crocks, it sold out in two hours.

Related: In Ballina, Father and Son Do It All at Seven Mile Brewing Co

The barrel-aged Stone Beer is one example of how in recent years Stone & Wood has diversified with greater frequency. The experimental Pilot Batch series, for instance, has taken off since Stone & Wood opened in late 2018 its beautiful new $3 million facility—the brewery’s “spiritual home”—on Byron’s outskirts. Though overall production in Byron hasn’t increased, a reallocation of brewing space between Byron and the much-larger mothership brewery 50 kilometers north in Murwillumbah freed up room for different brews.

Kveik IPA, Fruit Salad Berliner Weisse, Red IPA, Coffee Milk Stout, and Sam’s Hoppy Ale are just a few of the small-batch Pilots poured exclusively at the Byron tasting room so far this year. It’s worth noting that Stone & Wood’s production brewers rotate three-month residencies in Byron, a period in which she or he takes a break from the higher-volume core beers brewed in Murbah and gets full ownership of the Pilot Batches, among other things.

In 2015, Stone & Wood joined forces with ex-Mountain Goat salesman Tom Delmont on Fixation Brewing Co, which only releases IPAs. Given the singular focus, it’s a good thing Fixation does it exceedingly well: At last year’s Australian International Beer Awards (AIBA), Fixation IPA earned the first-ever “Consistency of Excellence” award for bagging three straight gold medals in the IPA competition. Fixation’s core IPAs are brewed by Stone & Wood and distributed nationally, while The Incubator in Melbourne is the showcase venue with a small brewkit. Our last check showed Dark Menace Black IPA, Kiwi Kettle Sour IPA, and The All-American Cherrywood Smoked Rye IPA among the 10 IPAs on tap.

Last year Stone & Wood co-founder Brad Rogers launched a new brewery, Forest for the Trees, which does farmhouse, sour, and wild ales. It’s the latest venture folded into the Fermentum Group, the parent company that owns Stone & Wood, Fixation Brewing Co, distribution leg Square Keg, and other brands. Forest for the Trees’ first two releases were the 4.7% Saison and 7.2% Barrel-Aged Saison, the latter a blended saison fermented in French oak barrels for six months. I can’t wait to get my hands on these.

To celebrate its tenth anniversary, last November Stone & Wood released SWX, a big 10% imperial stout aged for 10 months in fortified wine barrels. And in March, the Counter Culture series debuted with Killer Kween, a 7.6% imperial Berliner Weisse brewed with 1.2 tons of raspberries. Sticky Nectar, a hazy 6.5% IPA with “truckloads” of mango puree, followed in May, and then It’d be Rude Not To, a 7.4% pastry stout, arrived in July. The plan is to drop a new Counter Culture roughly every two months.

In a world flush with endlessly esoteric beer, this all might sound part and parcel for a modern craft brewery. Projects like Counter Culture, however, represent a measured leap of faith for Stone & Wood into a specialty market still far more niche in Australia than in North America and Europe. Though “craft beer” is on the upswing Down Under, it still only represents a fraction of the continent’s beer market.

Related: In Wellington, You Can Bet Your Bottom Dollar Garage Project Ain’t Going with the Rest

It’s no surprise, then, that hazy, fruity, sour, and big barrel-aged beers have been little more than a footnote for the better part of Stone & Wood’s decade-long existence, and to be clear they still are compared to the vastly higher production volume of top sellers Cloud Catcher (an Australian pale ale), Green Coast Lager, and Pacific Ale. It’s the last beer, Pacific Ale, that is the true breadwinner, accounting for roughly 90 percent of Fermentum’s annual 11-million liter output.

This is the beer upon which Stone & Wood built its modest empire. Defying easy classification, it’s a beer perhaps best described as a place, for if it was possible to bottle (or can) the Byron Shire, the shire would taste like Pacific Ale.

“There’s something about it that transcends age, gender, region… there’s just something about it,” says sustainability manager James Perrin. “We’re really focusing on the local area, but when you have a Pacific Ale it doesn’t matter where you are because it always draws you back to Byron and to this eastern coast of Australia.”

Byron in a Bottle

My wife may have best summed up Pacific Ale when she called it “bright, beachy, and Byron.”

“Pacific Ale is a dream to work with, as we believe there’s no beer in the world quite like it,” says Kasster Soh, co-founder of Singapore import and distribution company The Mad Tapper.

“When people take their first sip, we want them to be transported to that first beer they have when they emerge salty from the water, having just had a swim at Byron Main Beach on a late summer afternoon,” said co-founder Ross Jurisich in this Financial Review Stone & Wood profile.

“Pacific Ale doesn’t really fit into a beer style. It’s not a pale ale, it’s kind of its own thing,” says Jess Flynn, who helps manage Stone & Wood’s Byron tasting room and community outreach program. “It’s a name the boys made up, and we called it that because we think it’s the perfect beer to drink when you’re next to the Pacific Ocean, especially in a place like the Northern Rivers.”

Cloudy but not New England IPA hazy, equal parts hoppy and yeasty, and brewed with Australian malts, the 4.4% Pacific Ale is single-hopped with Galaxy, an Australian varietal that imparts ripe tropical fruit aromas and flavors. Stone & Wood sources these hops from Hop Products Australia, which manages more than 555 hectares of hop fields between its farms in Victoria and Tasmania.

In this Drinks Adventures podcast, HPA managing director Tim Lord claims the manner in which Stone & Wood so beautifully spotlights Galaxy in Pacific Ale can largely be credited for the hop’s increasing popularity abroad. “I used it relentlessly to show brewers [in Europe]. To this day it remains one of the very few beers in the world that you can take into a hop garden, grab a fresh Galaxy cone off a mature hop plant, rub it, smell it, and then open [the] beer and have a drink and people just get it,” said Lord. “It just reflects Galaxy really, really well.”

Pacific Ale first dropped on November 28, 2008, when it was tapped in Byron as Draught Ale at The Railway Friendly Bar (“The Rails”) and Great Northern Hotel. Stone & Wood co-founders Rogers, Jurisich and Jamie Cook renamed the beer once they started bottling it, and it has gone on to become one of Australia’s most popular craft beers. In fact, it has placed either first or second for eight straight years at the GABS Hottest 100 Aussie Craft Beers competition, an annual poll that in 2018 saw 31,000 people cast more than 155,000 votes for their favorite Australian craft beers. That’s no small feat since only 10 percent of Stone & Wood’s annual production is sold nationally; it is exported in small quantities to select markets that include Singapore, Hong Kong, and the United Kingdom.

Soh began importing Stone & Wood to Singapore in July 2017, adding the brewery to a portfolio that also includes such regional favorites as Garage Project, Pirate Life Brewing, and Yeastie Boys. “Pacific Ale is our best-selling beer in both bottles and draft, and makes up almost 80 percent of our Stone & Wood sales,” he says. “They make beers that are a perfect fit for the Singapore climate, and Pacific Ale is such a unique beer.”

Related: Bury Your Treasure, Burn Your Crops, Pirate Life Rising and It Ain’t Gonna Stop

Earlier I noted Pacific Ale takes 90 percent of Stone & Wood’s annual 11-million liter production. To give you a clearer sense of how that breaks down, consider that Stone & Wood’s Murbah brewery operates two 5,000-liter brewhouses in tandem and has 16 40,000-liter fermenters. On a normal winter day the brewing team—which comprises eight brewers for each shift—fills one fermenter and empties another for packaging. With a nod to its local focus and keeping its beer as fresh as possible, bottling/canning and kegging get a roughly 50-50 split, which means each 40K tank produces around 350 kegs and 2,000 cartons. Come summer, the team sometimes doubles daily packaging to 700 kegs and 4,000 cartons.

That may sound like a lot of beer (and a lot of Pacific Ale), and for Australian craft it certainly is, but it’s still but a drop in the ocean. When I visit the Murbah brewery, Perrin notes that with annual production of somewhere between 80 and 100 million liters a year, Coopers Brewery is by far the country’s largest independent brewery. Stone & Wood, with “just” 11 million, is the second biggest, and there’s a significant drop down to the next few. “We’re less than one percent of the total beer market, and yet we’re kind of the biggest of the small guys, so there’s still this huge room for growth,” he says.

Still, while Stone & Wood continues inching up production, Perrin says it does so cautiously.

“Brewing is a very capital-intensive industry. You’ve gotta outlay so much cash before you see any return. You see all these breweries around the world investing millions and millions into growth and expansion, and then maybe they don’t quite fill it, and that’s when they start discounting or selling out half stakes,” Perrin says. “The last thing we want to do is get too far ahead of ourselves and run into that financial constraint where you have to start looking for outside investors. Whilst we’re still growing well, we’re really monitoring that growth.”

Fresh Pacific Ale is one of the many great joys of visiting Byron Bay, where I genuinely feel it tastes like one of the world’s very best beers. Cloud Catcher, a 5% pale ale brewed with a mix of Galaxy, Enigma and Ella hops, is another absolute cracker. Crushing these two at places like The Rails and Beach Hotel—sometimes a few days or weeks after being kegged—is a special treat; grabbing fresh cartons at the tasting room and filling the fridge with “Byron in a bottle” is a luxury.

Importantly, these beers don’t just taste (really) good—they are, to again coin the village brewery’s phrase, a force for it.

Walking the Walk

“I’ve worked in other breweries and other industries, and then you come here, and sometimes I still kind of go, what’s the catch? It genuinely is a business that’s put its money where its mouth is,” says Perrin.

“I’m so stoked to come to work every day,” says Flynn. “I want to do my job well. I feel like I own my role, and I really care about the business becoming successful.”

James Perrin joined Stone & Wood in late 2015; Jess Flynn did so at around the same time. Like I’m sure most of their colleagues, neither seems to have any intention of leaving—more than 70 percent of the brewery’s employees are shareholders. Under the scheme, after one year on the job all employees are eligible to purchase shares, which are loaned interest-free and paid back over time; each new year brings an option to acquire more shares. After five years Stone & Wood offers an extra shares kick, plus springs for a paid two-week tour of historic local breweries in Germany.

Expenses for that annual trip are about to go up as Stone & Wood’s staff swells and sticks around. Perrin tells me that one person took it in 2016, three in 2017 and eight in 2018. “In four or five years’ time we’re going to have to charter our own flight,” he says.

“The idea is about seeing those multi-generational breweries that are integral in the community and doing good beer,” Perrin continues. “There’s one story about this head brewer over there named Fritz. His dad was Fritz and his dad was Fritz… there are five Fritzes, and Fritz’s eldest son, Fritz, is going to inherit the brewery next.”

Given the company’s priority on work-life balance and a host of other job perks that includes two cartons of beer a month, it’s no surprise staff speaks so rapturously about their employer. During her introduction on a guided tour one afternoon, Flynn calls the brewery’s co-founders “absolute legends” and says “they kind of remind me of the Care Bears in a really good way.”

“Brad [Rogers] is the friendliest and most amazing brewer you’ve ever met, and he’s able to foresee flavors and think of these really crazy combinations that always work,” Flynn says. “Ross [Jurisich] is this incredible, charismatic people-person who just makes you feel really valued in his presence, and Jamie [Cook] is the most incredible mastermind of business I’ve ever met. I hope he writes a book one day because the way he thinks about business is so innovative and inspiring.”

This story, or some version of it, is not uncommon, and though it may seem a little over the top, it always sounds genuine, unprompted. When I ask Soh how his relationship with Stone & Wood developed, he says it started over email, but took off after meeting the team in person. “We drank plenty of amazing beer along the way, but it was the culture of the company that really sold us,” Soh says. “The people were friendly and passionate, they loved and supported their local communities, and they believed in good beer. For us, working with good people ranks very highly.”

You may not care whether Stone & Wood are good people or not and only that it makes good beer, and that’s perfectly understandable. I think it does make a difference; treating employees and the local community fairly, honestly, and generously is crucial; it matters when breweries and businesses of any kind take great lengths to respect our fragile environment (more on this shortly).

These things are important in our increasingly fraught times.

“In this day and age, when we’re getting so much smarter as a society, we tend to crave a little bit more product knowledge,” says Flynn. “We want to eat grass-fed beef, we want to eat organic vegetables, we want to know we’re not supporting child labor by the clothes we wear. It’s the same with beer. We’re not just making beer to get people drunk, so we try as much as possible to be more than that.”

They certainly do.

Stone & Wood is a certified B-corp business, which according to B Corps means it “meets the highest standards of verified social and environmental performance, public transparency, and legal accountability to balance profit and purpose.” In 2017, it won the “Business Leadership Award” and “Premier’s Award for Environmental Excellence” at the Green Globe Awards.

This year, the aforementioned inGrained Foundation launched the Northern Rivers Large Grants Program, which invites local charities to apply for grants ranging from $15 to $30K to help bolster their regional social or environmental projects. The SHIFT Project Byron earned $27K to launch Linen SHIFT, which provides training, employment, and support to homeless or at-risk of homelessness women in Byron Shire. Shaping Outcomes, which manages early childhood intervention programs, and Bangalow Koalas were 2019’s other winning applicants.

Stone & Wood donates to various not-for-profit charities $1 for every 100 liters sold, and regularly sends its team out for beach-cleaning and other volunteer days. At the tasting room, merch is fashioned from organic cotton; even the toilet paper is sustainably sound. It’s difficult ticking off these achievements and initiatives without turning this into a public service announcement, but again, this is a conscientious business model worth celebrating. I haven’t even gotten to the brewery’s environmental focus.

Perrin earned a degree in chemical and environmental engineering at The University of Queensland. “We treat all of our wastewater onsite, because being a reasonably sized manufacturer in a very small town, we’ve got a very big footprint in terms of our waste and wastewater,” he says. “Last financial year we did a $500K upgrade of our wastewater treatment system, and we did a few hundred dollars in our boiler and gas systems to save energy, so that year we saw a 20-percent reduction in gas usage.”

According to Stone & Wood’s April 2018 Green Feet update, it uses 1.2 liters of water less than the industry average to produce a liter of beer, as well as 63 MJ/HL less energy than the industry benchmark to make 100 liters of beer. It aims to reduce each number even further by the end of 2020. Stone & Wood also reports that since mid-2015 its Murbah brewery’s 100kW solar system has essentially “mitigated CO2 emissions to the equivalent of planting 5,000 trees.”

Think back to those loads of bright and beachy Pacific Ale brewed and shipped out of Murbah. Perrin was part of a team that worked with an environmental consultancy to assess a bottle of that beer’s life cycle. The goal was to better understand its biggest carbonate energy impacts, from the bottle’s glass suppliers to distribution and disposal.

“It helps frame our thinking. We can continue to focus on getting our water usage down, or is that kind of like a red herring, and we’re better off working with suppliers to get more bang for our buck in that space?” says Perrin. “It’s going to shape up our thinking about what our sustainability projects should be focused on.”

Beyond the nitty-gritty environmental planning, Perrin tells me his job also entails connecting and working with Murbah commerce in ways that transcend his professional background. “A lot of this is new and exciting to me because it’s not just about how we want to grow our business, but also how to improve our systems in the community,” he says. “It means things like showing up at 6:30am on a Friday morning at a business chamber breakfast, being an active voice in that community and really contributing to the local region’s development. We want the entire village, the region, to be better off for us being here.”

“It’s just like the olden days in early modern Europe when you had the village butcher, baker, and brewer—we want to go back to that local brewer who is just adding value in tangible ways.”

#

On the other side of the planet, Pacific Ale is one of 20 beers on the board at The Earl of Essex, a buzzy, cozy pub located on a residential street in London’s Islington borough. The Earl added Pacific Ale as its permanent pale ale this May, a perfect marriage between my favorite London pub and one of my best-loved beers. On a beer board as varied as this one, though, Pacific Ale doesn’t stand out like it should, like it deserves. There are other pale ales, other cloudy and hazy beers, more familiar local breweries.

I order a pint, my last trip to Byron having ended just a week or so ago. I see a few others drinking Pacific, and assume they’re thinking it’s a great beer. As I take a few sips, I think about spotting wallabies and whales and kookaburras with my son on morning hikes at Three Sisters; about looking up into planetarium skies after sundown at Broken Head; and about trying to surf with a golden god from Perth.

###

Stone & Wood’s tasting room is located at 100 Centennial Circuit in Byron Bay. Open Monday to Friday 10am to 5pm, weekends 12pm to 6pm. Tours are AUD$25 and limited to 12 per session.

All photos taken by Brian Spencer and cannot be reused or published without permission.