“Whatever I say is completely irrelevant, and any brewery you talk to is just marketing. They’re just selling a story, true or not, interesting or not.” – Evin O’Riordain, Founder, The Kernel

In the 2003 Christmas special finale of The Office, the character Tim Canterbury, played brilliantly by then 32-year-old Martin Freeman, says that “life isn’t about endings; it’s a series of moments.”

There is only one ending in life, and the way in which each of us ultimately reaches it is punctuated by an endless tidal wave of moments, the significant and trivial and everything in between, that precede it. The occasions of chance; the incidents of triumph and defeat; the periods of mundanity and breathless adventure; we do not exercise imperforate control over the moments which make up life, but it is the minor and major choices we make—we the privileged, that is, that get to make choices that reach beyond basic day-to-day survival—that shepherd the unique series of moments that piece together, one by one, our individual puzzles.

Evin O’Riordain is acutely aware of the privilege of choice, and deeply meditates on the impact choice exerts on the moments that do and will shape his life, his family’s lives (“The choices you make and how they suddenly affect your kids as they get older become very important.”), and the footprint of his London brewery, The Kernel.

When O’Riordain and I meet three years after our first clipped email correspondence—more on that later—throughout our conversation the lean, bearded Irishman who balances deep, somewhat intimidating gazes with palpable warmth and sincerity carefully considers and chooses his words before speaking. When I ask pregnant questions that delve deeper than, say, the brewery’s specs (20 BbL brew kit, 10 fermentation vessels, 2 ex-red wine foeders), more often than not he pauses 10 to 15 seconds before answering. At times, he retraces his thoughts and restates the same answer, though slightly differently, perhaps because he feels he did not choose just the right words the first time.

Privileged moments of conscientious choice dictate direction in every life, or in this case every brewery, be it choosing the malt bill of a certain beer, the fermentation method for another, or the hops blend for still another. However, there is something notably… penetrating about the dynamic and defining role choice plays at The Kernel. Here choice is thoughtfully weighed and resolutely asserted. It is greatly prized above most other things—and what O’Riordain has done with the power of choice is establish not just one of London’s most-respected breweries but, more than that, a brewery and beers that embody a specific world view of time, community, culture, and consumerism.

A Lot of Small Movements

“The choices we make when we’re making a pale ale or porter are very much… well, you have a lot of control over that process. You spend most of your time keeping the air out, keeping bugs out, and things like that, whereas here you let [the beer] do what it wants to do. You’re more reactive.”

Jazz faintly humming into The Kernel’s chilly barrel-aging room from the adjacent production facility, fluffy efflorescence like tufts of powdery snow blanketing the wet and porous brick walls, O’Riordain sidesteps his way from behind a stack of old wine barrels now used to age the brewery’s house saisons. The Kernel began its barrel-aging program in 2012; today there around 80 barrels in use, plus the two aforementioned foeders.

“Back here you engage with it, so I suppose our sense of place comes from that,” he continues. “That you allow that sense of place to express itself… well, we don’t control it much, but you still make choices in terms of its maturation and the way it interacts with the environment.”

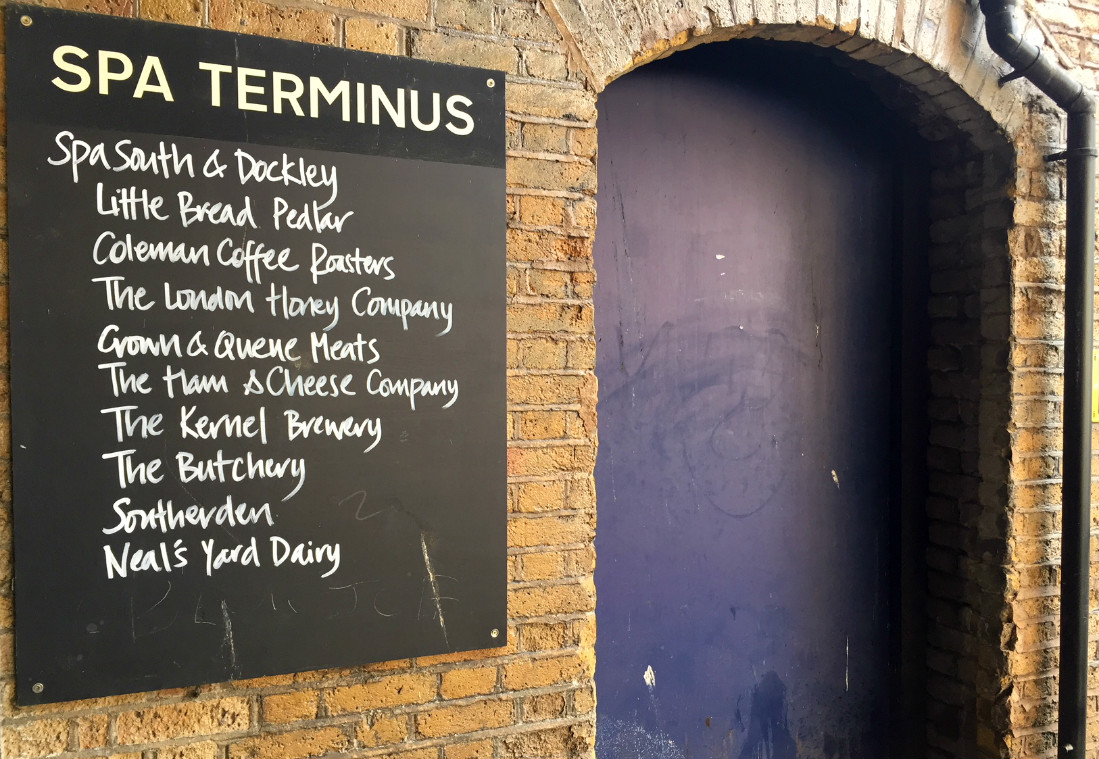

Situated underneath railroad tracks in south London’s rapidly gentrifying Bermondsey district, this space was empty for about six years before The Kernel relocated here from its original digs on nearby Druid Street. In one side of the unit, O’Riordain and his 14-person staff handle production and bottling of The Kernel’s range of what he simply calls “dark beers” and “pale and hoppy beers,” while such things as product storage, the barrels, and bicycles—most of the staff ride bikes to and from the brewery—take up the other side.

In the dank barrel-aging area of this Victorian-era archway, the brick walls have never been dry and it is always a little cool, regardless of the weather outdoors. O’Riordain, who for advice leans heavily on friends in noted Belgian lambic breweries like Brasserie-Brouwerij Cantillon, says that some brewers believe steady conditions like this benefit the beer’s in-barrel maturation process, while others favor seasonal shifts in climate. There is no right or wrong way to do it, in other words—it is only a matter of circumstance, approach, experimentation, and choice.

“If you go speak to the Belgians making more traditional gueuze or lambic, they’re in warehouses that get freezing cold in winter and really hot in summer. So they have really big temperature swings, which they say will kind of encourage some bacteria in the yeast when it’s warm, while other ones will have more of a chance when it’s cold, which is very true,” he says. “But then you talk to other people who say that, no, stable is good because you know where you’re at. You’re not going to get anything too crazy.”

At The Kernel, staff fills barrels with the saisons, often adds such fruits as sour cherries, raspberries, and apricots, then lets the beer rest for up eight or nine months before bottling it. Depending on the batch and style, the beer is on occasion dry-hopped, as well, then moves to the bottle for anywhere from six to nine months for further fermentation before it’s ready to make its public debut.

Related: Beavertown Brewery’s Tempus Project Turns One

“There is something quite specific to here and to the barrels. You can feel it, and you can taste it. We’ve had other people’s beer and we’ve brewed with others’ yeasts, but you stick those into our barrels and it comes out tasting like our saisons, even with new barrels,” O’Riordain says. “That’s our style, whether you like it or not, and in one way that is our sense of place. I think our pale ales and our dark beers have it, too, but not in the same way. We change our recipe for each batch, but still our pale ale will taste like one of our pale ales.”

O’Riordain pours glasses of Biere de Table Damson, a lilting, mildly sour 4.1% ABV saison aged with damsons, which are a subspecies of plums. It has a little sparkle, hints of funk, light fruit, and unmistakable overall subtlety. “These beers are supposed to be slightly tart and refreshing. There’s a lot going on, but it shouldn’t interfere with being able to enjoy something in a drinkable sort of way,” he says. “It’s a lot of work going into something that’s very delicate—eight months in a barrel, then eight months in a bottle—and yet you’re still not trying to make something that’s ‘wow.’”

The Kernel’s barrel-aging program continues growing in scope and focus, which reflects both the brewery’s maturation and, perhaps more than anything, the staff’s own fondness for these particular beer styles. Indeed, bottles of lambics, kriek lambics, gueuzes, saisons, and other barrel-aged brews dominate the brewery’s beer stash, and O’Riordain says that one reason the brewery doesn’t do many seasonal beers and only supports limited runs of dark beers is because he and his staff choose to prioritize what they themselves personally enjoy.

It’s probably not accurate to call this pivot to barrels a major change at The Kernel; barrels have been used here for six years now, after all. Rather, what at least appears to be a rising and gradual emphasis on barrel-aging in many ways epitomizes the brewery’s prevailing modus operandi. “A lot of the way we do things is sort of slow and steady. It’s not like you go to a point and then you turn; it’s more like a slow curve,” O’Riordain says. “You might end up somewhere else, but it’s more a lot of small movements.”

“I think our core principles are relatively the same. The beers have changed slowly, slightly, and the way we work has changed slightly. In that sense it’s hard to pin down any particular moments where we’ve changed course. I think closing the taproom was probably the most radical choice.”

More is Less

In 2014, BBC Travel commissioned me to write a short feature story on what at that time had just recently become known as the “Bermondsey Beer Mile.” At an Anspach & Hobday pre-launch party London blogger Matt Hickman coined the catchy colloquialism, a reference to the cluster of craft breweries located near one another in Bermondsey. Shortly after that Jack Hobday, one of the brewery’s co-founders, launched a bare-bones Beer Mile website that was little more than a treasure map leading to the area breweries.

The concept caught fire, with far more Londoners—and in some cases a far different crowd—flocking en masse to these breweries’ open-house taprooms on Saturday afternoons. It was good for business, sure, and still is, but it markedly changed what had previously been a fairly mellow scene and taxed the breweries’ staff and facilities, pushing some of them to reevaluate.

The Kernel was one of them. In fact, when I reached out to O’Riordain to discuss the story and to request an interview, he responded with an honest take on burgeoning Bermondsey, then politely declined. “I hope you understand why we really don’t want any further publicity for breweries in Bermondsey,” he wrote, “and why we’ll have to turn down your request for an interview.”

When we meet three years later, I tell him that I understood and appreciated his candor. “There was a certain point in time where it felt like—well, maybe never there was, as I may have been naïve—but I think around the time you would have gotten in touch there was still a feeling that if we all denied that the Bermondsey Beer Mile was a thing that everybody would forget about it,” he admits.

That, of course, didn’t happened. Hardly. In fact, over the past year Affinity Beer Co, Spartan Brewery, Bianca Road Brew Co, Moor Beer Company, London Beer Factory, Brick Brewery, and Small Beer have all set up taprooms and/or brewing facilities in Bermondsey, further transforming this area into what is almost inarguably the center of London’s ongoing brewing renaissance.

Related: In Bermondsey, A Belgian State of Mind at The Barrel Project

The Kernel was the first brewery to put Bermondsey on the map (at least in modern times). In mid-2015, it became the first to disengage from the Beer Mile phenomenon side of it when O’Riordain chose to close the Saturday taproom. Bottles are still available for takeaway, but that’s it.

“Far be it from us to dictate to other breweries how they work,” he says. “We were here and already established, so we could afford to close the taproom and still go on, whereas many of the others couldn’t or can’t. I wasn’t going to impose rules on how they work.”

Don’t confuse O’Riordain’s mild apathy for the Beer Mile conceit with animosity of his brewing neighbors. The Kernel very much remains a part of the community and maintains a particularly close connection with certain breweries, like Partizan Brewing and Brew By Numbers. O’Riordain himself has made a sizable impact on London craft beer and the careers of those driving it, a fact which Claire Bullen explores with aplomb in her in-depth origins story for Good Beer Hunting.

No, it is more that the “Bermondsey Beer Mile” is an antithesis vision in which O’Riordain does not see a place for The Kernel. Similarly, as London’s overall number of breweries crosses the century mark, O’Riordian also chooses to move to the periphery of another group—the London Brewers Alliance, of which The Kernel was one of a handful of founding members in 2010.

“The first few years we did a couple collaboration brews together, and still have a couple kegs of a stout hidden in the corner in that back room somewhere, so the fact that it’s been archived means something,” says O’Riordain. “But then two years later there were too many people and too many different agendas, and all it takes is one person to stand up and start yapping about whatever is annoying them, which is fine, but if it’s not annoying you and you don’t have the time…”

He stops to think before continuing.

“We’re just passive members these days. We just don’t have the time to engage, and we don’t necessarily see eye to eye with everybody.”

Press Play and Don’t Repeat

Lunch break at The Kernel spurs most of the staff upstairs to a loft commons area for cuts of envious cheese blocks from Neal’s Yard Dairy, one of the brewery’s neighboring tenants at Spa Terminus. Downstairs bottles of Export India Porter have rolled down the bottling line all morning, while here in the loft O’Riordain opens a bottle of El Dorado IPA. “This was packed nine or 10 months ago, so the freshness of the hops has faded down, but what happens is that the wild yeast starts chomping on hop compounds and creating other types of fruit,” he says. “That is… there’s a certain type of brett known for making pineapple-y things.”

Once this batch of this particular IPA runs dry, that’s it. At The Kernel, none of the beers are exactly replicated or reproduced, which helps explain how as of April 2018 the brewery can have more than 660 different beers listed on RateBeer. However, while no two Kernel beers taste the same or share a recipe, once they’re bottled they all look almost exactly the same. On the labels, which are like strips of brown paper bags, the name, hops used, and best by date are the only things that differentiate one beer from another—and, for the most part, that’s the only information the brewery chooses to include on the label, period.

In terms of packaging and marketing, if loquacious breweries like BrewDog and Stone sit at one end of the pendulum, The Kernel anchors the other.

“You can’t tell which is which, and we’re quite aware of that. It forces you to have to speak to a barman and ask—and I hate doing that, too,” O’Riordain says with a laugh. “I don’t worry about it; that simplicity is part of it. Most of the world tends to infantilize people to within an inch of their lives. It seems like the more information that can be thrown at somebody the better, but everybody is just bombarded with far too much of it, unless you turn off your computer and phone, which nobody does anymore.”

Unsurprisingly, The Kernel doesn’t have a Facebook page or Twitter account and only sporadically updates its Instagram. Its website primarily functions as a platform to announce events, new beer releases, and bottle availability for the weekly Saturday takeaway sales. It doesn’t have any stories about O’Riordain or the brewery’s history, no beer archive or descriptions, no merch for sale—just a short and simple one-paragraph mission statement. “The brewery springs from the need to have more good beer,” it begins.

“I suppose our entire momentum has come from word of mouth. We actively try not to promote ourselves,” O’Riordain says. “If somebody recommends one of our beers, hopefully it’s because they care about it, not because they think it’s trendy or saw somebody on TV blowing something up or driving a tank down the street—that’s too obvious.”

… And When the Wheel of Fortune Turns Progressively Depraved

From the basic need in 2009 to have more good beer in London, choice has propelled The Kernel into a series of moments that have in relatively short time forged a specific identity and reputation. O’Riordain chalks up at least some of the brewery’s success and impact to timing, noting that when the London Brewers Alliance first met in 2010 one could count the number of standalone breweries in the city on one hand.

“We aren’t the first, but maybe the first of a certain wave,” he says.

Related: A London Pub Chat with Matthew Curtis and Will Hawkes

When he singles out Fuller’s Brewery as one brewery that was particularly helpful in The Kernel’s early days, I ask if he could see The Kernel continuing on as Fuller’s has. That brewery started in 1816 as Griffin Brewery before becoming Fuller’s in 1845 following a change in ownership.

His answer is one part not really, and one part it won’t matter anyway.

“The brewery is not something that has been built to create its own value beyond to us that are working here. A lot of modern economics work on things having a value that can be passed on to somebody else, but to us if you sold the name of the brewery, for example, it doesn’t work anymore,” O’Riordain says. “In that sense, the brewery is certainly something beyond me. It should survive, but then you’re passing on to other people and it becomes something else, and that’s fine.”

However, O’Riordain feels that certain choices made across the world over time, from ignoring environmental health to electing dangerous people to positions of power, make any discussions about long-term beer and brewery futures moot.

“Environmental armaggedon will kill us all within 50 years. There will only be cockroaches left,” he says with a straight face. “Sorry, that was a bit harsh; I’m trying to think of a positive side to it. Before Mr. Trump came along we only had 100, and now we have maybe 65.”

###

The Kernel Brewery is located in Arch 11 at the Dockley Road Industrial Estate in Bermondsey, London. Pick ups are available at its Arch 7 Taproom (which opened after this story was published) daily from 10am – 5pm. Check the taproom website for drink-in hours.